Making meaning of love, loss, and breast cancer

- 11/09/23

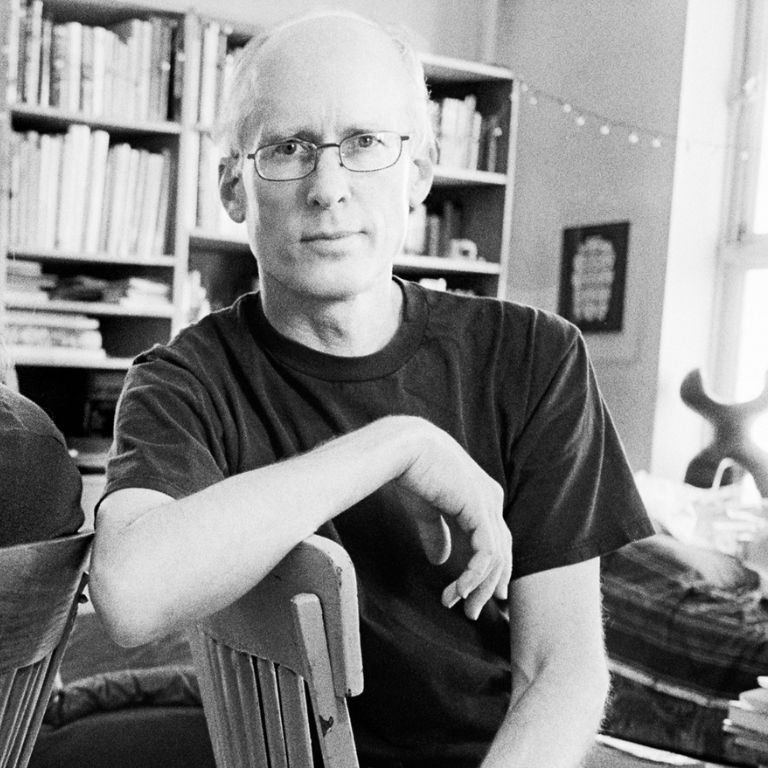

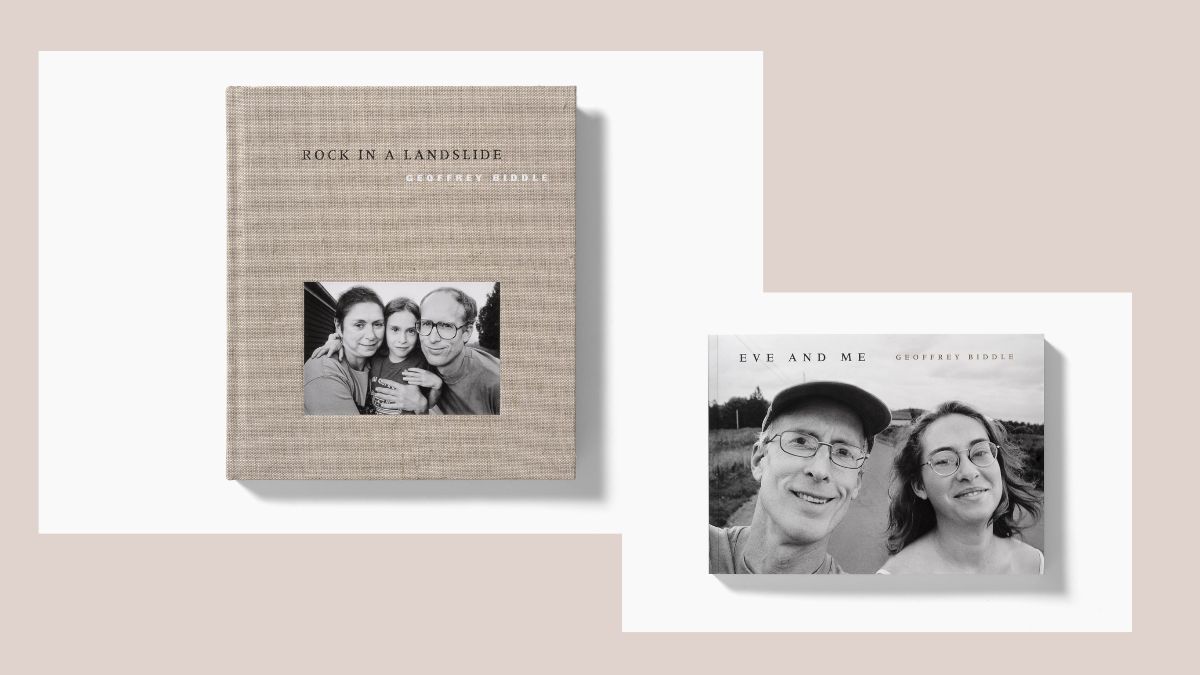

Photography helps me reflect on my relationships of love and care, and to process what’s confusing and overwhelming. Working with my photographs and writing in response to them has helped me work through loss and grief that never fully goes away. In my companion memoirs Rock In A Landslide and Eve and Me, I paired my photographs with written accounts of my wife Mary Ann’s breast cancer experiences 20 and 30 years ago. The distance of time has been clarifying and helped me make sense of the emotions so many families may experience—fear and determination.

Rock In A Landslide begins with romance: my moving to New York and falling in love with the sculptor Mary Ann Unger. I recount our charged partnership, our parallel creative practice, and the East Village factory space we reclaimed together as a shared studio and home. Our “Great Collaboration” was daughter Eve, whose joyous birth was too soon darkened by Mary Ann’s diagnosis and thirteen-year journey of treatment and recurrence.

Eve and Me is a series of father/daughter self-portraits, beginning with Eve’s arrival and concluding twenty-two years later with her graduation from college. I wrote the brief accompanying texts directly to Eve. They illuminate the sweet, sometimes happy, sometimes painful and poignant details we shared during those years. The book traverses our life together from city playgrounds to country fields, without and within the shadow of illness and loss.

Care wears many hats. When someone is sick in your family, everyone needs to be cared for, and many of us take on the role of caregiver—the healthy spouse, the children, even the person who is sick cares for those who care for them. These few excerpts from Rock In A Landslide and Eve and Me are snapshots of my cancer experience, what my family faced, how we coped, how we took care of ourselves and each other. Some of these stories are big and dramatic, others are made of the little things that happen every day. I am grateful that I have my photographs to prompt memories, guide my account, and tell stories of their own.

Me and Mary Ann, 1980. From Rock In A Landslide

When she got the biopsy results I was away on assignment, just like three years earlier when she told me she was pregnant. This time I was on a pay phone, in a Minneapolis bar where I was grabbing dinner, when Mary Ann told me the lump was cancerous and she needed surgery. A young drunk waiting to use the phone was angry I was taking too long and overheard what I was saying. He leaned in close and yelled, “Thanks a lot! I need to call my mother! She’s in the hospital with cancer!” It was a grotesque intrusion on our conversation, yet emblematic of how our lives had tipped into the incomprehensible, a mix of the painful, noble, and absurd.

Mary Ann, 1986. From Rock In A Landslide

I shared the many jobs of parenthood and took on contending with Mary Ann’s medical bills. My membership in a professional photographers’ association gave us access to health insurance, and even though the premiums exceeded childcare as our single largest expense, we knew we were lucky to have it. I had to become expert in the health insurance system of the 1980s, maintaining compulsively thorough logs of correspondence and phone calls. I learned never to pay a hospital bill before the insurance reimbursement because it was impossible to get money back if I overpaid, and that saying “cancer” made collection agencies back off.

Mary Ann, Eve and me, 1989. From Rock In A Landslide

In spring of 1988, breast cancer recurred and metastasized in Mary Ann’s bones. We spent that summer at her parents’ suburban New Jersey home, back into the nest, where two solicitous and caring people fed us meals and watched over six-year-old Eve. Mary Ann rested between treatments and would ask me to lie down with her midday to “absorb my energy.” I liked the closeness, and energy was something I could give her. I relieved my angst and replenished myself by swimming a hundred laps at a go in the small backyard pool, back and forth, over and over, eight strokes from one end to the other.

Eve, Mary Ann and me, 1992. From Eve and Me (text from Rock In A Landslide)

Eve needed our help processing her mother’s illness. From early on, she understood Mary Ann was battling something that could kill her. The question none of us could say out loud was, “When?” Our uncertainty was exaggerated by a tacit agreement not to talk about death, a silence Eve was indoctrinated into and adopted. There were inevitable questions as she became more aware and able to express herself. We presented optimism, emphasizing our unity and the fact that Mary Ann was alive now and could live for many more years. We did our best to be honest and also reassuring about our family stability even in the face of cancer. But each of us was followed by an unwanted shadow. When she was nearing ten, Eve came into our bedroom and showed us she’d found hard nodules behind her nipples. We all three went to a doctor who quieted our fears, explaining the lumps were breast buds and completely normal. Eve could sense our worry. She told me years later she brooded over losing both parents and dying young herself.

Mary Ann, 1997. From Rock In A Landslide

By mid-autumn the doctors told us we should join home hospice.

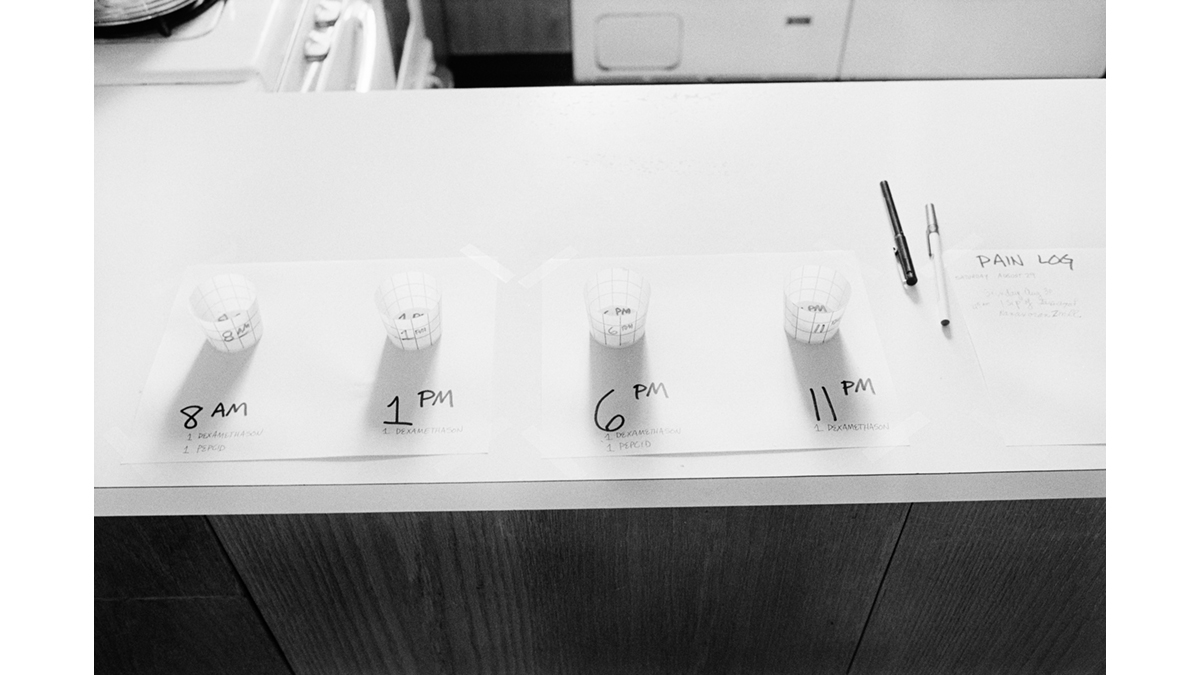

Medication, 1997. From Rock In A Landslide

Busyness at home was as much a buffer as going to work. Do the pills chart, manage the nursing service, keep a log of when Mary Ann took her meds and what she ate and when she eliminated.

It was hard to feel tender and connected in the fog of duties and obligations. On the other hand, doing everything I did was its own way of saying, “I love you.” …. I hope Eve saw how our strong marriage prevailed, however altered. The same love that startled me when I first saw Mary Ann, that delighted me when Eve arrived, that inspired me to mend things when we needed counseling, saw me through those final years, then months.

Mary Ann (right) and her mother, 1998. From Rock In A Landslide

…. A lot had happened in that room. Mary Ann and I made love there and had terrible arguments. We welcomed our child into the bed when she had nightmares, and for a few years we snuggled together on Thursday nights to watch The Simpsons. This room was where I took care of Mary Ann, where the north-facing industrial windows and the hospital bed became the entirety of her world, a world that once spanned the globe, whether she was trekking Nepal or crossing the North African desert alone.

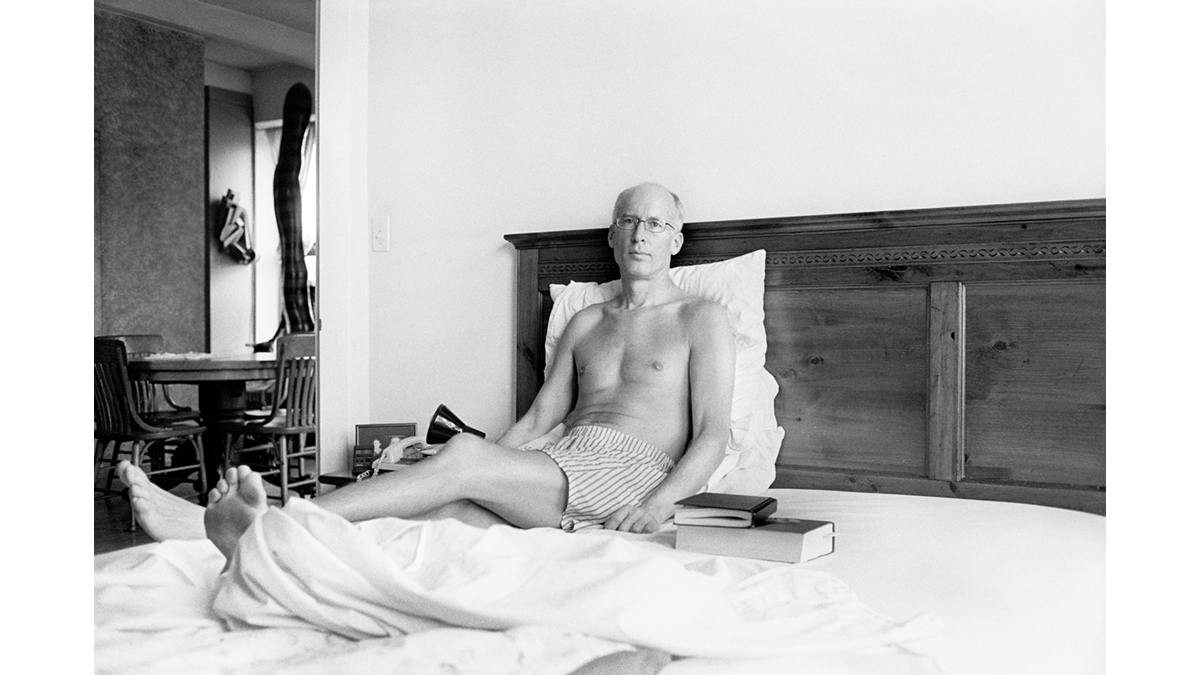

Me, 1999. From Rock In A Landslide

I’d manage five or six drinks, stumble off to bed, and sleep heavily until snapping awake the next morning. On the way to work, I often cut through the auto repair shop across the street and said hello to John and Angel, the owner and one of his mechanics I’d gotten to know over the years. They knew what was going on in my life. One morning as we stood together in a bay door, Angel asked me how I was doing and I told him, “I’m drinking a lot.” He scrutinized me and then said, straight from an AA script, “You can’t mourn when you’re drinking.” Angel was a recovering drug addict who’d recently had a fistfight with a policeman over a trivial parking dispute. Maybe not the obvious guide to help straighten me out, he identified the problem in one short sentence.

Eve and me, 2001. From Eve and Me (Texts adapted from Eve and Me and Rock In A Landslide)

Mary Ann’s sculpture is in the window and my three-part portrait of Eve is above the mirror. The past stayed with us as our lives moved on.

Mary Ann still comes to me in dreams. Sometimes it’s at my mother’s house, on the brick patio overlooking the field, a beautiful day with a lunch party where the dead and the living commingle. Sometimes it’s in the loft and I’m with Mary Ann. Dreams are made up of pieces of time and experience, organized yet open for interpretation—like photographs. If I put my pictures in chronological order, people appear when they’re born and disappear when they die, neat and definitive and not like life. My mother and father are both dead, and they are still with me, just as Mary Ann is still part of me and my family. I made these books to understand how she fits in, and as the story continues to unfold, I go on taking pictures.

Please share your thoughts and reactions to these photographs and book excerpts. I’d be honored to hear from you. You can find my contact information at geoffreybiddle.com, where you can also order Rock In A Landslide and Eve and Me.

The texts adapted from Eve and Me and Rock In A Landslide are reproduced here with permission from the author.

DISCLAIMER:

The views and opinions of our bloggers represent the views and opinions of the bloggers alone and not those of Living Beyond Breast Cancer. Also understand that Living Beyond Breast Cancer does not medically review any information or content contained on, or distributed through, its blog and therefore does not endorse the accuracy or reliability of any such information or content. Through our blog, we merely seek to give individuals creative freedom to tell their stories. It is not a substitute for professional counseling or medical advice.

Stay connected

Sign up to receive emotional support, medical insight, personal stories, and more, delivered to your inbox weekly.